In the early fifth century, the See of Antioch claimed ecclesiastical supremacy over the Church of Cyprus, and as a bitter conflict emerged, the matter was eventually presented before the Council of Ephesus. This article outlines and analyzes the historical sources and events, with a particular emphasis on its relevance in contemporary Malankara.

2025-01-19

Background: 1st-4th Centuries

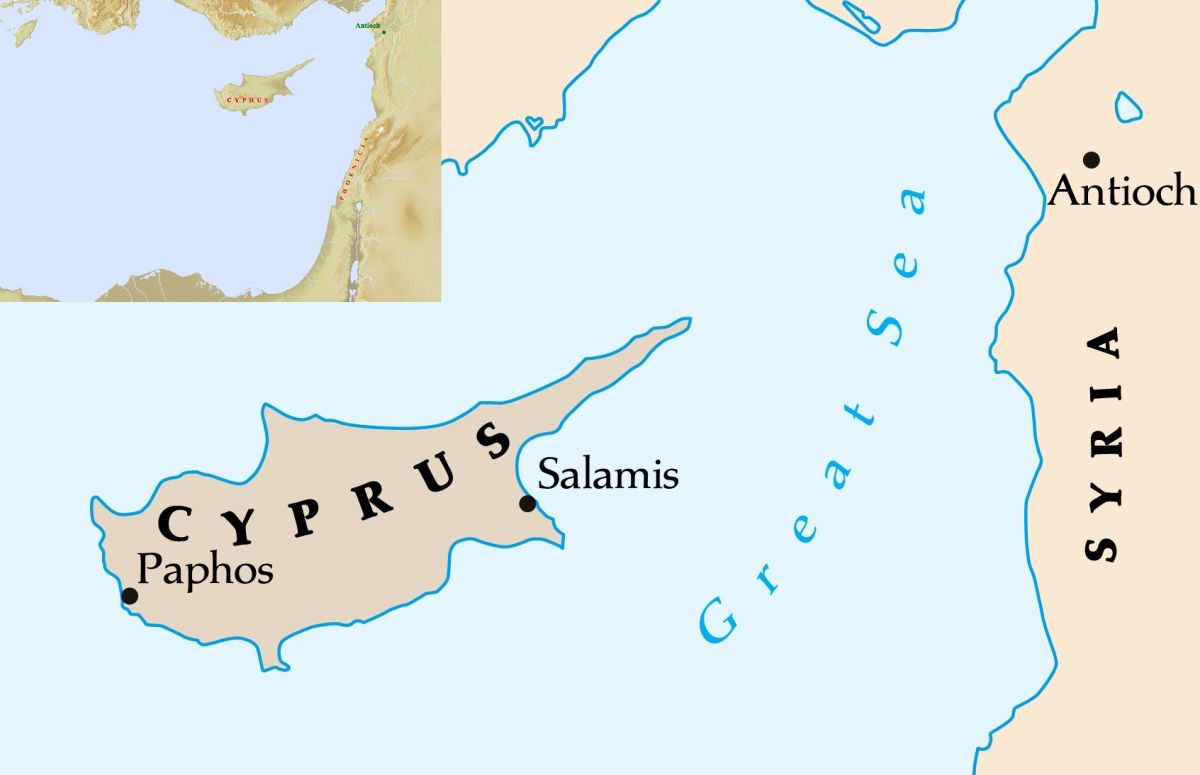

Christianity reached Cyprus shortly after the Resurrection of Christ, as attested by the Acts of the Apostles. Apostles Paul, Barnabas, and John Mark preached in Salamis and Paphus, the two major cities in Cyprus (Acts 13:4-12). The text later briefly mentions that after the Council of Jerusalem, a conflict arose between Paul and Barnabas, resulting in the parting of their ways, and Barnabas sailed to Cyprus along with Mark (15:39). Indeed, this would be expected by the readers who are informed beforehand by the text that Barnabas was "a Levite from Cyprus" (4:36).

Given this apostolic background, it is unsurprising that the Christian community of Cyprus flourished through the centuries. By the third century, the island was home to multiple episcopal sees, two of which — Salamis and Paphus — were represented at the Council of Nicaea by their metropolitans. The Synodical Epistle of the anti-Origenist Council of Alexandria of 400 CE, presided over by Pope Theophilus of Alexandria, names fifteen bishops of Cyprus among its recipients.

Pat. Alexander of Antioch and Jurisdiction of Cyprus

The Churches of Cyprus and Antioch were geographic neighbors, and the reported ancient custom that, from time to time, the Cypriots received holy chrism from Antioch, seems quite probable due to this proximity (George Hill, A History of Cyprus, Volume 1: To the Conquest by Richard Lion Heart, p. 278).

From a certain point in time (more precisely, in late-fourth or early-fifth-century), however, the See of Antioch began to consider Cyprus as part of her jurisdiction, and intended to formally incorporate the island's episcopal sees as dependent dioceses. Pat. Alexander I of Antioch (r. 413-421) was the first to stake claim over Cyprus, and he wrote a letter to Pope Innocent I of Rome sometime around 415 CE asserting the same. Though Pat. Alexander's letter is not extant, its contents may be reconstructed and understood from the Pope's reply (preserved in Latin), relevant excerpts of which are translated and provided below.

Both the burden and the honor imposed on us by your brotherhood has prompted the causes of this necessary treatise, so that we may respond to your letters or memorandum as the grace of the Holy Spirit provides. Therefore, reviewing the authority of the Nicene Synod, which explains the mind of all priests throughout the world, which decreed concerning the Church of Antioch what is necessary for all faithful, not to mention priests, to observe, which we recognize as established over the aforementioned Diocese, not over any single province. .. Therefore, dearest brother, we judge that just as you ordain metropolitans by singular authority, so too you should not allow other bishops to be appointed without your permission and knowledge. In this matter you will rightly observe this method: that you decree those who are far away to be ordained through letters by those who now ordain them by their judgment alone; but for those nearby, if you think it appropriate, you should arrange for them to come to your grace for the laying on of hands. .. For as to what you inquire, whether, when provinces are divided by imperial judgment so that two metropolises are created, two metropolitan bishops ought to be named; it has not seemed right that God's Church should be changed according to the mobility of worldly necessities, or undergo honors or divisions which the Emperor has deemed necessary to make for his own reasons. Therefore, according to the ancient custom of the provinces, it is proper that metropolitan bishops be counted. You assert that the Cypriots, formerly exhausted by the power of Arian impiety, did not observe the Nicene canons while ordaining bishops for themselves, and until now have maintained the presumption that they ordain by their own judgment, consulting no one. Therefore, we persuade them to take care to understand according to the Catholic faith of the canons, and to be of one mind with the other provinces, so that it may appear that they too, like all Churches, are governed by the grace of the Holy Spirit. (PL 20:547-551)

It appears that the Patriarch made two major claims with respect to the supposed subordinate position of the Church of Cyprus. One, since the civil Province of Cyprus was part of and subordinate to civil Diocese of Oriens (i.e. grouping of administrative provinces in the Roman Empire) headquartered in Antioch, the episcopal sees of Cyprus should also have the same relation towards the See of Antioch. Pat. Alexander interpreted the Sixth Canon of the Council of Nicaea which provided for the See of Antioch (as well as all episcopal sees) to retain its traditional "privileges", as referring to her religious jurisdiction over the whole Diocese of Oriens.

Two, that when the Church of Antioch was internally divided during the Arian Controversy, the Cypriots began to ordain bishops for themselves (thereby disregarding the "Canons of Nicaea", or more accurately, Antioch's interpretation of the Canons), a practice that continued up to the time of his letter. In other words, the Church of Cyprus was effectively autocephalous: as Pope Innocent summarizes, "they ordain by their own judgement, consulting no one" (Lat. ut suo arbitratu ordinent, neminem consulentes).

The See of Rome agrees wholeheartedly with the Patriarch, apparently without any cross-checking, and concludes that the Cypriots must submit to Antioch. As we will see, Antioch would soon make the formal effort to force the metropolitans of Cyprus to acknowledge her superiority. In the meanwhile, however, a new ecclesial controversy was brewing up in Christendom.

The Nestorian Controversy

Following the passing of Pat. Sissinius of Constantinople in late 427, Emperor Theodosius II summoned Nestorius, the superior of a monastery near Antioch, on the recommendation of Pat. John I of Antioch (r. 429-441), to succeed Sissinius. A couple of months later, Nestorius was visited by a delegation who requested his advice on an important theological point: Should the Blessed Virgin Mary be called Theotokos ("she who bore God") or Anthropotokos ("she who borne man")? The Patriarch opined that Christotokos ("she who bore Christ") was the better title. Soon after, Anastasius, one of Nestorius's clerical associates from Antioch, preached to a crowd that since "Mary was only a human being", it is impossible that she could give birth to God, and therefore should not be called and revered as Theotokos. Much of the clergy and laity were troubled by this new teaching.

The imperial city was by now embroiled in this conflict, and the news of it spread across the Mediterranean. The mighty Pope St. Cyril of Alexandria, the vigilant champion and custodian of the patristic mysteries, took notice of Nestorius's teaching, and began composing treatises and pastoral letters critiquing his position, and upholding the unity of the Incarnate Word and his birth from the Virgin. The copies of these works reached an irritated Nestorius, who shortly afterwards received a personal letter from Cyril, advising him to amend his theological line and put an end to the scandal. By this point, both positions had hardened, and Cyril began to marshal international support against Nestorius.

![]()

Pope Celestine I of Rome supported Alexandria, and Cyril — after convening a Synod in Alexandria — composed the Twelve Anathemas against Nestorius, which were delivered to him. As it became clear that an Ecumenical Council would be convened by imperial decree in Ephesus to discuss the matter, Nestorius forwarded Cyril's Twelve Anathemas to Pat. John of Antioch, and the See of Antioch formally supported Nestorius's dyophysite cause against Alexandria and Rome (Norman Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, p. 39).

By early June of 431, the bishops began to gather at Ephesus, and Cyril arrived with fifty of his suffragan bishops. The Council was summoned and presided over by Cyril, and all one-hundred-and-ninety-seven bishops who assembled at the first session agreed with him and condemned and deposed Nestorius. Pat. John who arrived a couple days later was enraged, and convened a rival synod in support of Nestorius, pronouncing the deposition of Cyril. Further sessions of the Council continued in Ephesus, until imperial officers arrived and arrested both Cyril and Nestorius to reduce the tension. Nevertheless, the relevant matter here for us is how one of these sessions of the Council dealt with Antioch's claim of jurisdiction over Cyprus.

Bishops of Cyprus and Synodical Hearing

Three metropolitans of Cyprus, led by Reginus of (Salamis-)Constantia, attended the Council of Ephesus. Reginus was particularly invested in the theological controversy, having delivered a homily attacking Nestorius's dyophysite position at an earlier session. During a session on August 31 (or July 31, if we are to follow the hypothesis that "August" is a copyist error), the bishops of Cyprus informed the Council concerning their troubles with Antioch, and presented a petition which was read aloud. Hereafter, we will quote from the Acts and Proceedings of the Council and comment accordingly.

Reginus bishop of the holy church of Constantia in Cyprus said: ‘Since certain people are causing trouble to the most holy churches in our province, I ask that the petition which I have to hand be received and read.’

The holy Council said: ‘Let the petition you have brought be received and read.’

"To the most holy and glorious and great Council assembled by the grace of God and at the bidding of our most God-beloved Emperors in the God-protected metropolis of Ephesus, a petition from Reginus, Zeno, and Evagrius, bishops of Cyprus.

Some time back our holy father Troilus, on becoming bishop, suffered countless hardships from the clergy of Antioch and the most religious Bishop Theodotus; for he was subjected, lawlessly, groundlessly, and uncanonically, to no slight violence even to the point of blows which it would have been improper to inflict even on criminals. For when he visited them on some other business, which was concluded successfully, they took advantage of his visit and tried to force the holy bishops of the island to become subject to themselves, contrary to the apostolic canons and the decrees of the most holy Council of Nicaea. And now, on hearing that the blessed one had come to the end of his life, they have made the most magnificent general Dionysius send directives to the governor of the province and an official letter to the most holy clergy of the church of Constantia, which we have to hand and are ready to show to your holinesses.

For this reason we beg and beseech you to allow no innovation to be imposed by those who think they should stop short of nothing, being men who from the beginning and from of old have wanted, contrary to the ecclesiastical canons and the statutes issued by the most holy Fathers assembled at Nicaea, to trample the great and holy council by means of wholly improper decrees. For as we have said, the most magnificent general Dionysius, a man entrusted with responsibility for military matters alone, would not have been incited today and taken up what does not concern him, since he has no standing in ecclesiastical affairs, if he had not been deceived by the most sacred bishops assembled there and their clergy, and so come to think it canonical (as his directives state) that a bishop should not be appointed in Constantia the metropolis of Cyprus without their approval. We request that the letter of the most magnificent general be read, together with the directives and all the missives and proceedings relating to this drama, so that your holy and great council may learn from them that overwhelming force has been used, for no slight turmoil has convulsed the wholly metropolis. Moreover we inform your holy council that with the letters of the most glorious general was sent a deacon of the holy church of Antioch. We therefore prostrate at your holy feet and petition that by a canonical decree even now - just as from the beginning and from apostolic times, in accordance with the ordinances and canons of the most holy and great Council of Nicaea, our council in Cyprus has remained free from harm, from plots and every kind of oppression - so now also through your impartial and most just decree and your ordinance we may obtain justice." (Richard Price, The Council of Ephesus of 431: Documents and Proceedings, pp. 525-527)

In short, the bishops and clergy of Antioch were effectively persecuting the metropolitans of Cyprus, including their late Primate, in order for "the holy bishops to become subject to them". The See of Antioch then apparently influenced general Dionysius to pressure the Church of Cyprus into refraining from electing and consecrating a bishop by themselves. Decrees from him instructing the Cypriots to wait concerning the matter of consecration until the Council assembles at Ephesus are presented and read. Following this, the Council begins the discussion.

The holy Council said: ‘What is it that the bishop of Antioch wants?’

Evagrius bishop of Soli in Cyprus said: ‘He is trying to take control of our island and arrogate the consecrations to himself, contrary to the canons and the custom that has prevailed from the beginning and from of old.’ (Price, The Council of Ephesus of 431, p. 529)

The Council then passes on inquire the historical details.

The holy Council said: ‘Is it clear that the bishop of Antioch has never consecrated a bishop of Constantia?’

Zeno bishop of Curium in Cyprus said: ‘They are unable to prove that from the time of the holy apostles an Antiochene has ever presided or consecrated or communicated with the island over a consecration, or anyone else.’

The holy Council said: ‘The holy Council is mindful of the canon of the holy Fathers assembled at Nicaea at that time in defense of the privileges of each church, where it mentions the city of Antioch. Inform us, therefore, if it is not the case that of ancient custom the right to carry out consecrations in your province has been vested in the bishop of the church of Antioch.’

Bishop Zeno said: In anticipation [of this question] we have testified that he has never presided nor performed a consecration either in the metropolis or in another city, but the council of our province assembles and appoints our metropolitan according to the canons. We request that your holy council ratify and confirm this, so that the ancient customs that prevailed may prevail even now, and so that our province may not be subjected to innovation by anyone.’

The holy Council said: ‘May the most God-beloved bishops please give further information: by what council were consecrated Troilus of sacred and blessed memory who has now passed away, or his predecessor Sabinus of holy memory, or their predecessor the renowned Epiphanius?’

Bishop Zeno said: ‘Both the holy bishops now mentioned and the most sacred bishops before them and those from the time of the holy apostles, all of whom were orthodox, were appointed by those in Cyprus, and neither the bishop of Antioch nor anyone else ever had occasion to carry out consecrations in our province.’ (Price, The Council of Ephesus of 431, pp. 529-530)

The gathered bishops, including Cyril (or if he was absent, Juvenal of Jerusalem), sought to clarify and confirm that the right to consecrate bishops for Cyprus has not been vested in the Patriarch of Antioch since the ancient times. In response, Zeno of Curium states that the latter has never performed a consecration for any of the episcopal sees of Cyprus.

Since we do not have a clear historical record of how the Church in the island functioned — both spiritually and administratively — during the first three centuries, it is difficult to determine whether Zeno's statement that none of the bishops of Cyprus from the first through the fifth centuries were consecrated by the Patriarch of Antioch is accurate. It seems likely that the Christian communities of Cyprus were spiritually dependent on Antioch at least temporarily in the early period, which could explain how the custom of receiving holy chrism from Antioch may have emerged. Nevertheless, what is also clear is that the Church of Cyprus remained largely independent, since her metropolitans are never listed as being under the jurisdiction of Antioch or belonging to the civil Diocese of Oriens in the synodical lists, including that of Nicaea (Glanville Downey, "The Claim of Antioch to Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction over Cyprus" in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 102:3 [1958], p. 225). Besides this, we will encounter yet another reason to question Antioch's claims.

Conciliar Resolution and Aftermath

After receiving this confirmation from the Cypriot metropolitans, the Council proceeds:

The holy Council said: ‘Our most religious fellow-bishop Reginus and the most devout bishops Zeno and Evagrius with him from the province of Cyprus have drawn attention to a matter that is an innovation contrary to the ecclesiastical statutes and the canons of the holy Fathers and touches the freedom of all. Therefore, because general ailments require a stronger remedy, since they cause more harm, and since it was not the ancient custom that the bishop of the city of Antioch should perform consecrations in Cyprus, as we have learnt from the petitions and personal statements of the most devout men who have appealed to the holy council, those who preside over the holy churches in Cyprus are to enjoy protection from outrage and violence, and are to perform the consecrations of most devout bishops by themselves and according to the canons of the sacred Fathers and ancient custom. The same is to be observed in the other dioceses and provinces everywhere, so that none of the most God-beloved bishops is to take possession of another province that was not from the beginning and from of old under his authority and the authority of those before him; but if anyone has taken possession of a province and made it subordinate to him by force, he is to restore it, lest the canons of the Fathers be contravened and through a pretext of priestly function the pomp of worldly power creep in, and lest unawares we destroy little by little the freedom that was bestowed on us with his own blood by our Lord Jesus Christ the liberator of all mankind. It has therefore been resolved by the holy ecumenical council that each province is to preserve pure and inviolate the rights it enjoyed from the beginning and from of old according to the customs formerly prevailing, while each metropolitan is free to take a copy of the proceedings for his own assurance. If anyone produces a decree at variance with what has now been laid down, the entire holy ecumenical council resolves that it is invalid. (Price, The Council of Ephesus of 431, pp. 530-531)

This resolution would be numbered as the Eighth Canon of Ephesus 431 in canonical corpora.

Now, Fr. Price translates Gr. εἰ μηδὲ ἔθος ἀρχαῖον as "since it was not the ancient custom", implying that the Council is absolutely and unconditionally ruling that the Patriarch of Antioch did not consecrate the bishop(s) of Cyprus, as the Cypriot metropolitans have attested. However, εἰ is more commonly used as "if", in which case the clause is conditional, and is to be translated as "if it was not the ancient custom". Downey 1958 translates the text in this latter manner, and posits that the Council's resolution is contingent on whether it was the right of the Patriarch of Antioch to consecrate bishop(s) for Cyprus since the early times. Therefore, it is fitting that we may not make a firm deduction either way (i.e. interpreting the resolution as being unconditional or conditional). Nevertheless, the ruling being noncontingent is more probable than being contingent, since (a) particular focus is laid on τῶν λιβέλλων καὶ τῶν οἰκείων φωνῶν (lit. "the petitions and their own voices") of the Cypriot bishops as evidence, and (b) the concluding clause — ἕξουσιν τὸ ἀνεπηρέαστον καὶ ἀβίαστον ("[they] shall have the indisputable / unimpeachable [right]") — is clearly definite.

It is crucial to note that while the Council was requested only to intervene in a particular matter of conflict of jurisdiction, it authorized and passed a general and inviolable rule for the autocephaly of Churches: no bishop is to claim jurisdiction over another diocese / province which was not under his authority from the ancient times, and if he has already done so, he is to restore the native Church's autocephaly.

Quite surprisingly, Pat. John of Antioch — though not part of the Council — did not protest this decision, at least publicly. He ikely had more pressing concerns with the rulings and resolutions of the pro-Cyrillian metropolitans than the matter with Cyprus, especially since enforcing control over the Cypriots was no longer practical. In fact, when the Patriarch lists the provinces under his jurisdiction later in a letter to Pat. Proclus of Constantinople (d. 446), he does not include Cyprus, or even mention the recent conflict (PG 84:811-812). However, a few decades later, Pat. Peter the Fuller of Antioch (r. 471-488) made one more attempt to submit the Church of Cyprus to the See of Antioch. We do not know much about this attempt, since sources are quite hostile: but it seems clear that the contemporaneous "discovery" of uncorrupted relics of St. Barnabas from near Salamis-Constantia averted the Patriarch's attempt, as it further reinforced the apostolic origins of the Christian communities of Cyprus and their independence (Downey, "The Claim of Antioch", pp. 227-228).

Sometime after the Council of Ephesus, the forger of the eighty-four Pseudo-Nicaean Canons (known as "Arabic Canons") fabricated a canon, according to which the Cypriots are subject to Antioch concerning the consecration of their metropolitan(s). In my opinion, the forger was a Syrian Maronite or Melkite monk in the early Middle Ages, in which case it would make sense as to why he would stand for the historic claims of the See of Antioch.

Conclusion and Relevance in Malankara

Unlike Cyprus, Malankara's apostolic origin and foundation is historically clear and attested by several sources from the second-century CE onward. Both Syriac and Egyptian sources (inc. Pseudo-Zachariah the Rhetor and Severus ibn al-Muqaffa) from the Late Antiquity describe the "people of India" (or, as in al-Maqrizi, al-Hind) as self-constituted Christian communities, who depend on Alexandria or Persia at times when their bishop passes away and troubles arise due to the absence of a metropolitan (Pukadiyil Ittoop Writer, Ecclesiastical History of the Syrian Christians, pp. 112, 119; W. H. D. Frend, Rise of Monophysite Movement, pp. 356-357). Crucially, we find more than a dozen references to the Indian Christians in Syriac, Coptic, Armenian and Latin sources from the sixth through the thirteenth centuries: none of these sources — particularly the West Syriac Orthodox historians — describe Malankara as being under the jurisdiction of the See of Antioch. In other words, whereas for Cyprus we may grant a spiritual dependence on Antioch from an early period (especially given the geographic proximity), there is no evidence whatsoever to attribute a similar position to pre-Portuguese Malankara.

Like Cyprus, however, Malankara has been dependent on Antioch since 1660s (i.e. after the arrival of Pat. Gregorius Abdal Jaleel of Jerusalem) with respect to spiritual matters, including consecration of metropolitans (though this was not recognized as a "right" of Antioch until the 1800s) and chrism. From this period onwards, we find Syriac Orthodox sources considering Malankara to be a part of the jurisdiction of the Maphrian-Catholicate of the East. The fact that this claimed jurisdiction was not — at least wholly and effectively — accepted by the native Church is evident from numerous events, including (a) Mar Thoma IV formally limiting the Maphrian from doing anything in Malankara, including ordaining priests and deacons, without his permission, (b) Arthat Chepped-Padiyola (see Arthat Padiyola of 1807: Text + Translation + Commentary), (c) the numerous indigenous consecrations, e.g. those of Mar Thoma I, IV, VII, Mar Dionysius II, III, and IV, and (d) Mar Dionysius IV of Cheppad's reference to Antioch as a "foreign Church" and the precise declaration that "foreigners have no authority over this Church": see Rethinking the Ecclesiology of Mar Dionysius IV of Cheppad: An Appraisal.

Therefore, the rule of Ephesus 431 perfectly applies to the current situation and conflict within the Malankara Church, concerning whether she is included within the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Antioch and whether the latter possesses temporal authority over her:

The same [i.e. self-government and self-consecration] is to be observed in the other dioceses and provinces everywhere, so that none of the most God-beloved bishops is to take possession of another province that was not from the beginning and from of old under his authority and the authority of those before him.